The adequacy of capital to absorb losses – capital adequacy ratios

Click here to learn more about introduction of Basel Framework.

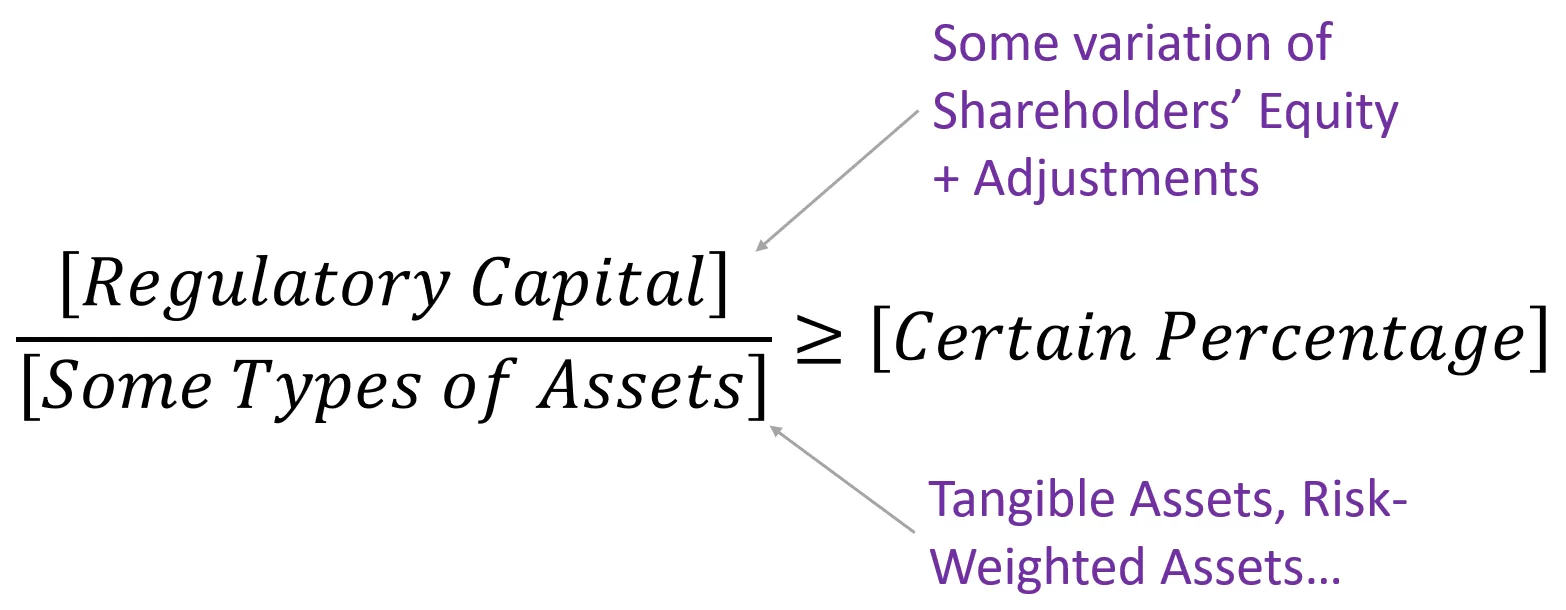

Capital adequacy ratios

As explained in “What is regulatory capital for?“, a bank must always maintain a certain amount of regulatory capital for unexpected loss. All these regulatory capital metrics and ratios are based on the bank’s equity.

Numerator: Some variation of Shareholders’ Equity + Adjustments

Denominator: Tangible Assets, Risk-Weighted Assets…

Examples:

- [𝑇𝑖𝑒𝑟 1 𝐶𝑎𝑝𝑖𝑡𝑎𝑙]∕[𝑅𝑖𝑠𝑘 𝑊𝑒𝑖𝑔ℎ𝑡𝑒𝑑 𝐴𝑠𝑠𝑒𝑡𝑠] ≥ 8.0%

- [𝑇𝑖𝑒𝑟 1 𝐶𝑎𝑝𝑖𝑡𝑎𝑙]∕[𝑇𝑎𝑛𝑔𝑖𝑏𝑙𝑒 𝐴𝑠𝑠𝑒𝑡𝑠] ≥ 3.0%

- [𝑇𝑎𝑛𝑔𝑖𝑏𝑙𝑒 𝐶𝑜𝑚𝑚𝑜𝑛 𝐸𝑞𝑢𝑖𝑡𝑦]∕[𝑇𝑎𝑛𝑔𝑖𝑏𝑙𝑒 𝐴𝑠𝑠𝑒𝑡𝑠] ≥ 4.0%

Good news is you don’t need to calculate these ratios yourselves. Banks will disclose these ratios in their financial filings. For instance, Citigroup 10-K 2021 page 33, Bank of America 10-K 2021 page 71, and Wells Fargo 10-K 2021 page 6.

The Numerator in Capital Adequacy Ratios

With the numerator, the main distinction that you have to think about is, “Is this capital available to absorb losses when the bank is still up and running, or is it only available in a bankruptcy / liquidation scenario?”

Some variation of Shareholders’ Equity + Adjustments, such as:

- CET1 (Common Equity Tier 1) Capital

- Tier 1 Capital

- Tier 2 Capital

- Tangible Common Equity

CET1 (Common Equity Tier 1) Capital and Tier 1 Capital

You can consider CET1 (Common Equity Tier 1) Capital and Tier 1 Capital as “Going Concern Capital”.

The assumption that a company has the resources to continue operating in the foreseeable future

Definition of Going Concern

Tier 1 Capital mostly consists of Shareholders’ Equity, and subtract out Goodwill, Other Intangibles and a few other adjustments. The reason we must subtract Goodwill and other Intangibles is because:

- whatever was spent on acquiring those is not available for the loss absorption

- in the denominator of this with Risk-Weighted Assets.

Goodwill and Intangibles don’t show up in Risk-Weighted Assets because they have a risk weight of ZERO. They also don’t show up in Tangible Assets because we subtract them out. Therefore, this is done mostly for consistency and to reflect the fact that they’re not truly available for the loss absorption.

The reason it’s called “Going Concern Capital” is under normal circumstances, a bank can take some of what the bank has saved up, set it aside and use that to cover their losses. The bank doesn’t have to go bankrupt to tap into this. They could just use it on an everyday basis, and that is exactly the idea behind Tier 1 Capital.

Tier 2 Capital

Tier 2 Capital consists of Hybrid Instruments mostly convertible bonds and other securities like that, that have some element of equity mixed with debt; Subordinated Notes, some portion of the Allowance for Loan Losses, and then various Reserve-type items.

So this is called Gone “Concern Capital” because a bank is never going to be able to tap into these types of things unless it is literally about to go bankrupt and it’s saying, “Okay, we can’t repay all of our creditors, but maybe we can repay 50 cents on the dollar to this one or maybe we can repay some of this to this one.“

These are not available for a loss absorption when the bank is running and healthy. These only come into play when the bank gets to the stage where the bank shut down and liquidate everything. At that stage, the bank can use some of these for our loss absorption. As a result of the loans going bad, the bank couldn’t repay the full amount, but the bank can repay 80%. It’s not what their lenders wanted but at least the lenders get some money back.

Refer to the above illustration, the Provision for Loan Losses is not really allowance. It’s an expectation of future results, but it doesn’t mean the company has lost anything yet. Therefore, it can count toward the “Gone Concern Capital”. When the bank is healthy, it shouldn’t be drawing on this to cover these losses. When the bank is now shutting down and selling off everything calling in on all its loans, it doesn’t need the allowance anymore. So now it can draw on this and use it to absorb these losses.

An accounting term for a company that has the resources needed to continue to operate indefinitely until a company provides evidence to the contrary, and this term also refers to a company’s ability to make enough money to stay afloat or avoid bankruptcy.

Definition of Gone Concern

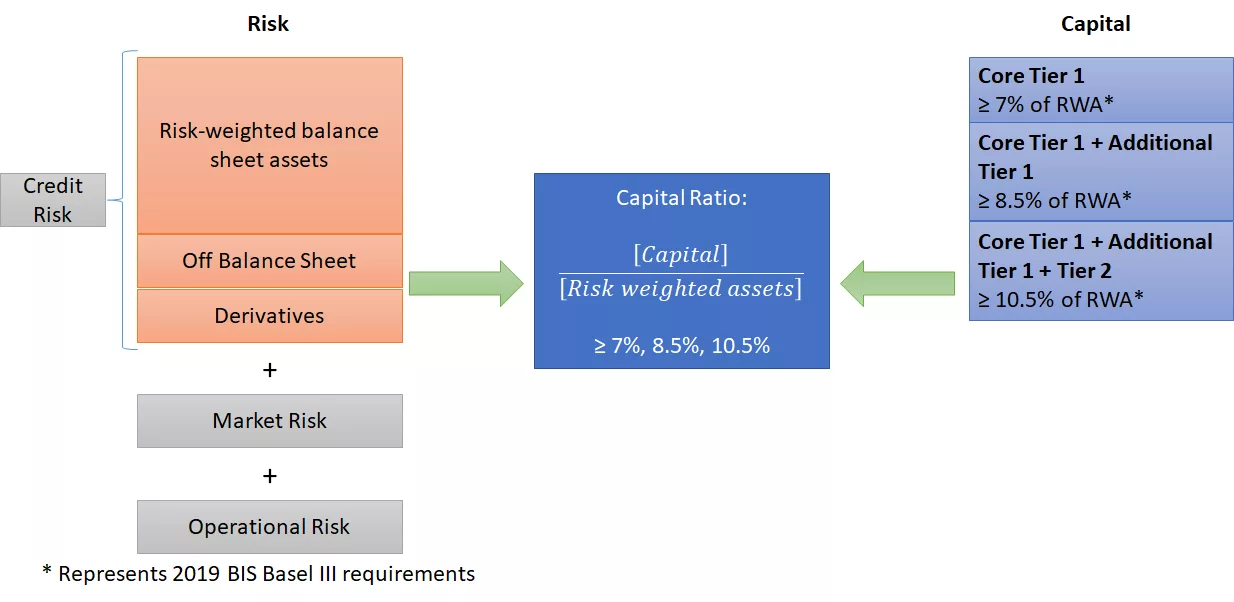

The Denominator in Capital Adequacy Ratios

The common denominator in capital adequacy ratios is Risk Weighted Assets (RWA). RWA is risk weighted, higher risks higher weightage.

A bank’s assets typically include cash, securities and loans made to individuals, businesses, other banks, and governments. Each type of asset has different risk characteristics. A risk weight is assigned to each type of asset, as an indication of how risky it is for the bank to hold the asset.

To work out how much capital banks should maintain to guard against unexpected losses, the value of the asset (ie the exposure) is multiplied by the relevant risk weight. Banks need less capital to cover exposures to safer assets and more capital to cover riskier exposures.

| Risk Weight | Example Assets |

|---|---|

| 0% | Cash and equivalents |

| 0% | Loans guaranteed by government |

| 0-150% | Loans to foreign governments |

| 20% | General obligation loans to state governments |

| 20% | Loans to other domestic banks |

| 20-150% | Loans to foreign banks |

| 50% | Qualifying first-lien residential mortgages |

| 100% | All other residential mortgages |

| 100% | Corporate/retail loans |

| 0-100% | Conversion factor for off-Balance Sheet items |

| 100% | Anything not in a pre-assigned category |

| 100-1,250% | Certain unsettled transactions |

What If a Bank Doesn’t Comply with These Rules?

| Ratio / Requirement | Well Capitalised | Adequately Capitalised | Under Capitalised | Significantly Under Capitalised | Critically Under Capitalised |

| Common Equity Tier 1 Ratio | >= 6.5% | >= 4.5% | < 4.5% | < 3.0% | Tangible Equity / Tangible Assets <= 2.0% |

| Tier 1 Capital Ratio | >= 8.0% | >= 6.0% | < 6.0% | < 4.0% | Tangible Equity / Tangible Assets <= 2.0% |

| Total Capital Ratio | >= 10.0% | >= 8.0% | < 8.0% | < 6.0% | Tangible Equity / Tangible Assets <= 2.0% |

| Leverage Ratio | >= 5.0% | >= 4.0% | < 4.0% | < 3.0% | Tangible Equity / Tangible Assets <= 2.0% |

| Supplemental Leverage Ratio | N/A | >= 3.0% | < 3.0% | N/A | N/A |

- Restrictions on dividends, acquisitions, and share buy-backs… and even compensation (in Europe under CRD IV)

- Higher deposit insurance premiums

- Possible government takeover if things get bad enough.

How does Tier 1 Capital Impact Dividend Payout?

For a normal company, you can assume a payout ratio and use that to calculate dividends. For a bank, you would calculate Tier 1 Capital with all the changes and additions from that year, except for dividends.

For example: Assume the bank has RWA of $1,000, and $130 of Tier 1 Capital. The bank is targeting a 12% Tier 1 Ratio, so it needs to always maintain Tier 1 Capital of $120. The bank can only issue $10 worth of dividends that year – issuing anything beyond that would reduce Shareholders’ Equity, therefore reducing its Tier 1 ratio to below 12%.

| RWA | Tier 1 Capital | Target Tier 1 Ratio | Tier 1 Capital to be maintained |

|---|---|---|---|

| $1,000 | $130 | 12% | $120 |

Dividend allowed = $130 – $120 = $10

Bank Bail In – Waterfall

Ever since subprime crisis, Basel III place higher emphasis on bail-in, rather than bail-out. Why punishes taxpayers?

A bail-in is rescuing a financial institution on the brink of failure by making its creditors and depositors take a loss on their holdings. A bail-in is the opposite of a bail-out, which involves the rescue of a financial institution by external parties, typically governments using taxpayers’ money. Typically, bailouts have been far more common than bail-ins, but in recent years after massive bailouts some governments now require the investors and depositors in the bank to take a loss before taxpayers.